June 2, 2022

By Rob Mitchum

The part of the world now known as Afghanistan was home to some of the earliest human communities, dating back as far as 50,000 years. But today, the country’s ancient sites are under constant threat, as wars, religious extremism, agriculture, and development lead to the destruction of irreplaceable artifacts and architecture.

In 2015, the US Department of State and the US Embassy in Kabul awarded the University of Chicago Oriental Institute a grant to launch the Afghan Heritage Mapping Partnership (AHMP), which uses satellite imagery to discover and monitor sites of cultural importance in the country. Recently, members of the Research Computing Center have joined that collaboration, bringing in the latest computer vision approaches to help the team meet its goal of surveying Afghanistan’s more than 650,000 square kilometers.

With the RCC’s help, the AHMP has sped up their process fivefold, finding tens of thousands of potential new archeological sites and automating the monitoring of areas in particularly severe danger. In just two months, the AI-based site detection method has added 11,900 candidate sites to the AHMP dataset, narrowing the areas that the human researchers must subsequently validate.

“What we found is that it’s so much faster to check a site that has already been proposed, than it is to look at a whole region,” said Gil Stein, Professor of Near Eastern Archaeology in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations and at the Oriental Institute and Principal Investigator for the Oriental Institute’s cultural heritage preservation grants in Afghanistan. “We’re hugely excited about this collaboration.”

In mid-May, researchers from the OI and RCC presented these early results to visitors from the Department of State. Teodora Szasz, Computational Scientist for Image Analysis, Visualization, and Machine Learning at the RCC, used the tiled wall display of the Data Visualization Lab to fly across the Afghanistan landscape in Google Earth, zooming in on satellite images of mounds, caravanserai, forts, and qanat — a pipeline system used for water transport and irrigation in ancient agriculture.

Thousands of years later, the computational pipeline built by the RCC team intakes several different types of imagery used by AHMP, including declassified spy plane photographs from the Cold War, hand-drawn topographical maps, and modern satellite and LIDAR scans. Trained on 3,200 sites labeled by human researchers, the pipeline utilizes high-performance computing resources to scan the entirety of Afghanistan, cut up into 70 million individual tiles, in roughly a week, finding similar structures.

Each pass of the model generates areas of interest for manual validation, which creates new labeled data to improve the model even further. In some cases, the model even goes beyond human ability, using the LIDAR data to recognize evidence of ancient sites that wouldn’t have been visible to the naked eye.

“This has been a great collaboration, one that I could not have imagined before,” said H. Birali Runesha, Associate Vice President for Research Computing and Director of the Research Computing Center. “It brings together expertise from computer vision, AI, GIS and archaeology, and the team has achieved great results. But more importantly for me, this collaboration has great potential for broader impact beyond my expectation. I can envision how other researchers in archaeology and other disciplines can make use of the methods and pipeline the team has developed.”

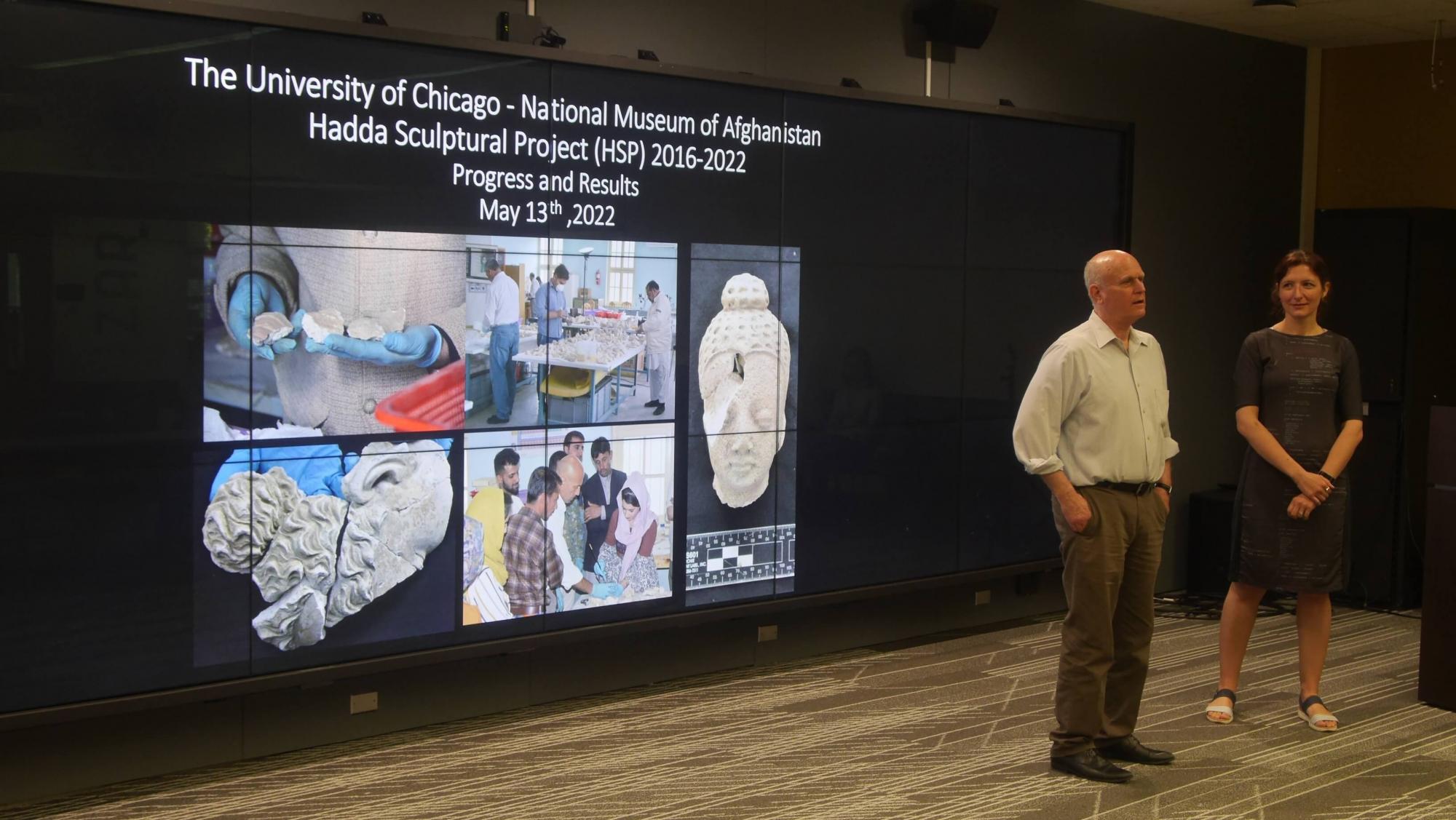

The RCC collaboration with AHMP was not the only OI project presented during the visit that uses modern technology to study the ancient world. Another collaboration, between the University of Chicago and the National Museum of Afghanistan, uses 3D imaging, hologram projection, and digital archives to help reconstruct statues from the Hadda archeological site shattered into thousands of fragments during the Afghanistan Civil War. Even after the setbacks of the COVID pandemic and the Taliban’s return to power, the international partnership continued through virtual conferences and computational tools.

“The Taliban in a weird way did us a favor that we can now see inside these sculptures,” Stein said. “We can see impressions on the insides of the sculpture, reconstructing the production steps for how these ancient craftsmen built the sculptures of Hadda. That helps us understand these artifacts not as individual sculptures, but as products of people in a community, interacting with monks and the monastery.”