February 14, 2025

By Jeremy Sykes

Reducing the time to perform scientific research in the study of cyclones and hurricanes with Professor Dorian Abbot.

Hurricane Helene at landfall as seen on the KTLH radar loop from 0252Z to 0308Z. National Weather Service Tallahassee, Florida, Federal Aviation Administration, and United States Air Force.

Hurricane Helene at landfall as seen on the KTLH radar loop from 0252Z to 0308Z. National Weather Service Tallahassee, Florida, Federal Aviation Administration, and United States Air Force.

The summer of 2024 marked a singular occurrence in weather–movie weather–history: Lee Isaac Chung’s film Twisters, racked up over 80 million dollars at the box office in the US. In the film, storm chasers are a mix of scientists and thrill seekers, risking their lives to try and capture these dangerous natural phenomena on film.

Hollywood aside, much of the current research on “extreme Mesozoic weather” is actually done with simulations run by supercomputers.

We are particularly interested in studying rare weather events with AI weather models. AI models are trained on data, so they haven't seen rare events often, or in some cases ever. This means they can't be expected to perform well on these events, which happen to have the largest impacts on humanity. Since AI weather models are 100,000 times faster than normal weather models, we want to find ways to improve their behavior on rare weather events,

said Dorian Abbot.

Dorian Abbot is a professor in the University of Chicago’s Department of Geophysical Sciences, studying climate, paleoclimate, and planet habitability. Abbot’s writ goes from Mesozoic storms on Earth all the way to orbital instability on Mercury. Abbot has partnered with the Research Computing Center (RCC) on a variety of ventures. Mohsen Zand, a computational scientist at the RCC, worked with the team. “I helped ensure that the computational setup met the specific demands of the research, particularly when scaling to the RCC’s A100 and H100 GPUs.” The RCC team worked effectively on enormous volumes of training data from a variety of resources, including the National Weather Service and the National Hurricane Service. They developed a unique mechanism to modify the training dataset in light of the project objectives.

We met with Professor Abbot to discuss the necessary software and hardware needs. We then facilitated access to the machines, ensured the software was properly set up, and helped finetune his simulation algorithms to run efficiently on our clusters and ACCESS resources,

said Zand.

The work began with the study of rapid intensification mechanisms. Abbot and colleagues developed a process called action minimization, which was built to create models of storms that could be computationally less expensive to run and analyze.

Abbot and the team’s action minimization process yielded a huge reduction: about a tenfold savings in computation time! This earlier success proved that huge gains could be realized in computing resources through changes in the algorithm.

In later work however, Abbott began to work with a Monte Carlo method of statistical sampling, developing something called Quantile Diffusion Monte Carlo (QDMC). Essentially the Monte Carlo method means having a computer drawing randomly from a sample, again and again, and developing probability statistics on the random draws. The QDMC method, while mathematically complex, is based on a fairly simple set of discrete rules. First, you set a target, in this case, the “rare weather event.” Then, you make the draws and plot them, and then “kill” the data points that move further away from the target.

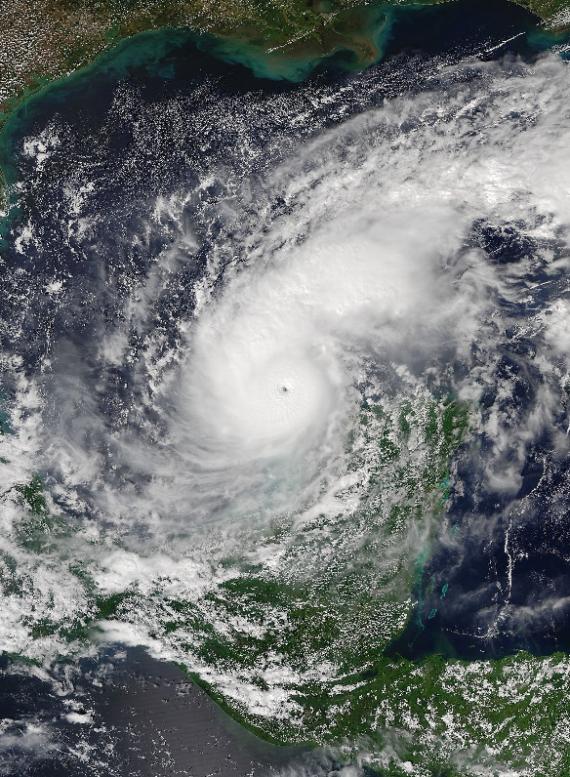

Hurricane Milton, VIIRS imagery from the NOAA-21 Satellite.

Hurricane Milton, VIIRS imagery from the NOAA-21 Satellite.

Massive hurricanes like Milton and Helene are perfect examples of the sort of phenomena QDMC is meant to predict, storms that build up extremely quickly and for which municipalities have little or no time to prepare. Following up on this work, Abbot and co-author Robert J. Webber at the University of California, began to think about how such algorithmic practices could be useful in other types of storm analysis.

For many potential extreme weather events, no historical analog exists. Storms can occur in surprising places. … Even when historical data are available, measurements can be sparse and sometimes corrupted.

(Weber, et al. (2019))

Working with the RCC was critical to both efforts, one of which required a hundred GPU nodes, running for 48 hours. “Zand played an important role in the project. He set the model up and trained the simulations on the GPUs,” affirmed Abbot. Ultimately, scientists get a data set with a much better error rate, which is predictive further out and for a fraction of the cost.

The RCC’s Zand, created and edited this fascinating YouTube video explaining some of the work done on RCC machines in this area.

Time savings on the operations of large clusters is beneficial to everyone. Scientists can more quickly run more simulations on a particular dataset, they gain greater accuracy, and tools like QDMC allow them to focus on new areas. This is good news for the institution and its researchers: managing the cluster, they can take on more research, accelerating the pace of computational experimentation.