by Benjamin Recchie

by Benjamin Recchie

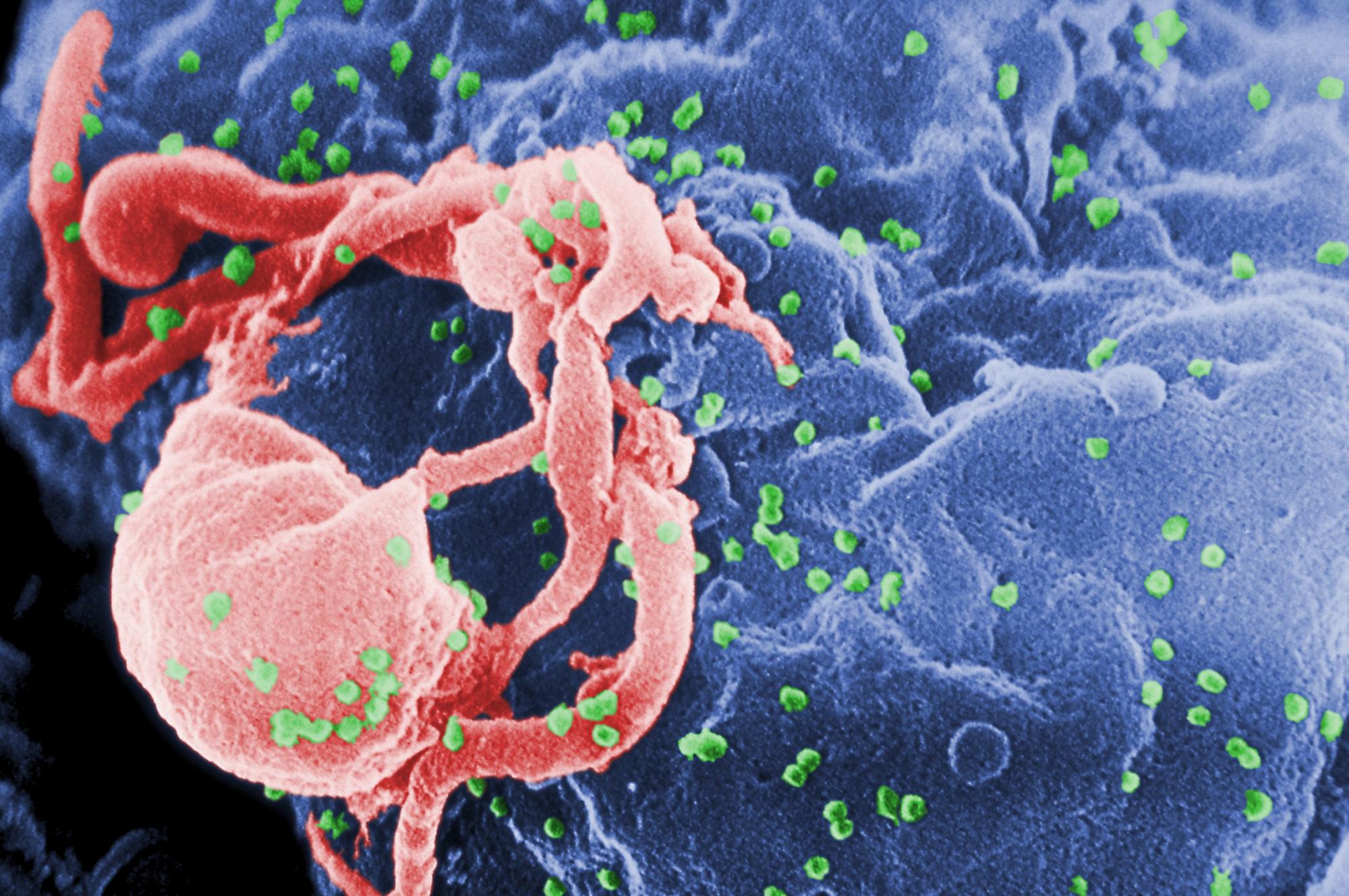

Viruses aren’t the only things that spread through a community. Knowledge can, too, if it starts with the right people. Public health authorities have long tried to disseminate information to as many people as they could in hopes of reaching the right eyes and ears. But now, a team led by John Schneider, associate professor of medicine and epidemiology and director of the Chicago Center for HIV Elimination, together with postdoctoral scholar and computational epidemiologist Aditya Khanna, and Stuart Michaels, senior research scientist at NORC at the University of Chicago, along with an interdisciplinary team of researchers, are conducting a massive study on the South Side of Chicago. Their goal is to find the key individuals in the community who can spread that information, in the hopes of launching a surgical strike against the spread of HIV.

The researchers are focusing on younger (ages 16 to 29) African-American men who have sex with other men (or MSM for short) who live on Chicago’s South Side. Besides being virtually in the University’s back yard, this group has the unenviable distinction of being “the leading edge of the epidemic,” says Michaels. Despite having lower risk factors than MSM in general, he explains, “the rate of HIV new infections in young black MSM is the highest of any single group.”

HIV treatment has improved dramatically in the last decade, says Schneider. People who are HIV positive can take pharmaceuticals that suppress the virus—in the language of researchers, an “undetectable viral load.” With the virus inactive in the person’s body, not only is he able to lead a normal life, but he’s not capable of transmitting the virus, either. Likewise, a daily pill called a pre-exposure prophylactic, or PrEP, can be used to protect someone who isn’t infected with HIV from contracting it from someone who is.

Together, these drugs give public health authorities powerful tools to blunt the spread of HIV/AIDS. However, these men face many barriers that might impact their ability to take their medication, such as housing instability or incarceration, factors that need to be considered when planning an intervention. “Many of these men have managed to take their medications and maintain viral suppression despite being targeted by the criminal justice system,” says Schneider.

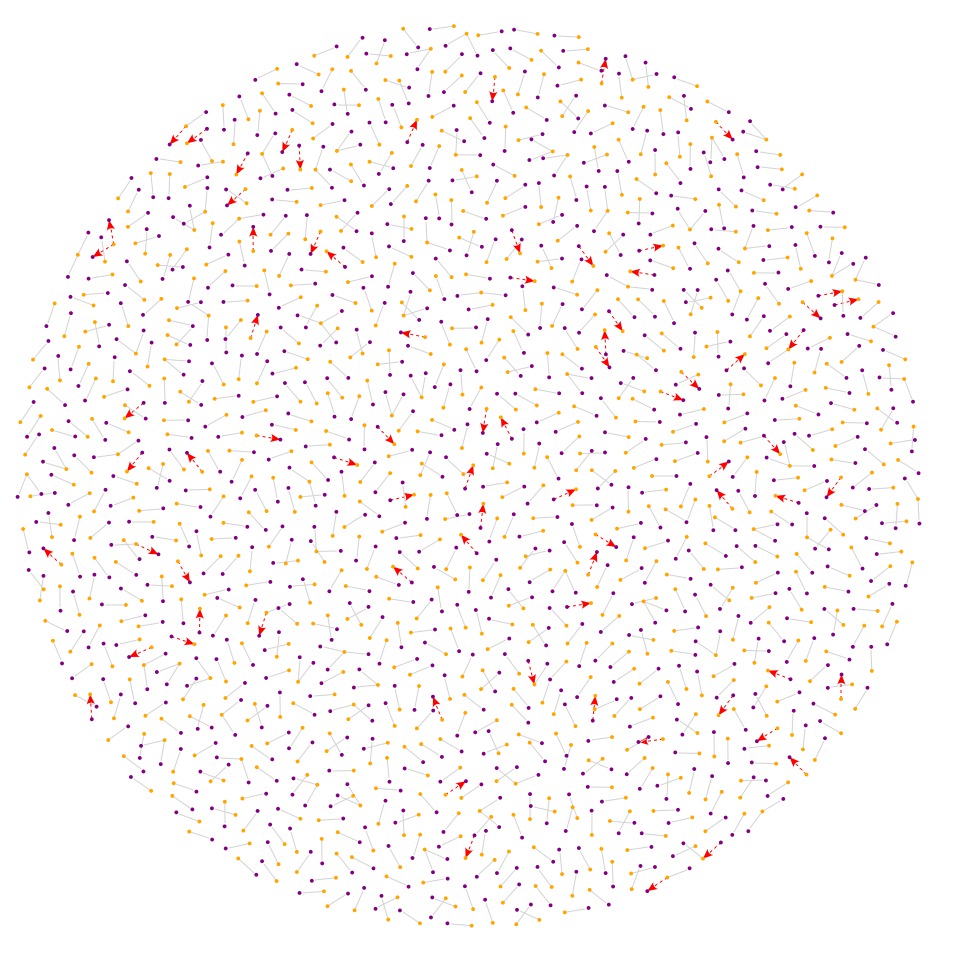

The researchers are focusing on social networks of the men in their study. They have, what Michaels says, is the “largest sample of young black MSM of any study in a single locale,” over 620 people, or an estimated 10% of the entire such community. To understand their social networks, the researchers have asked the participants to grant them access to the Facebook friend lists. They were able to get data from about 300 people, or just under 50%, with an average of roughly 1000 friends each. Traditionally, social scientists would sit down to map all of the relationships in a sample by hand. But with thousands of potential relationships, that wasn’t feasible. Instead, they turned to the Research Computing Center for help computing the probabilities that the (Facebook) friends of Facebook respondents were also friends with each other.

Network-based simulation of heterosexual HIV transmission based on data from Uganda. Orange dots represent men, purple dots represent women, and connecting lines show long-term sexual partnerships. The red dashed arrows are partnerships between infected and uninfected individuals, with a non-zero transmission probability. The arrow points from an HIV-infected to an HIV-uninfected individual. Image courtesy of Aditya Khanna and Simon Jacobs.

Khanna had used supercomputing resources at the University of Washington while a PhD student; RCC consultant Simon Jacobs helped him to get his code working on Midway. “I was using a standard out-of-the-box method that was taking weeks to implement,” explains Khanna. “Simon worked on it for three days and found a solution that worked in ten minutes.” The resulting gain in efficiency meant the researchers could analyze their results much more swiftly, giving them far more flexibility to explore new ideas. Jacobs and Khanna are now writing home-grown tools to analyze the network positions of actors within large social networks.

The ultimate goal of the project is to be able to identify the key people in this community whom public health authorities should work with to maximize the usage of antivirals (for those who have HIV) and PrEP (for those who don’t). One obvious solution that’s been used in the past is recruiting people who have reputations as leaders in the community, says Michaels, but that might not be the best way. “Network theory actually suggests some counterintuitive solutions,” that might be more effective, he says. “Maybe it’s not just the star—maybe it’s actually people who are in other network positions,” such as “bridges,” individuals who connect otherwise separate groups to each other.

![example_net[1].jpg](/sites/rcc.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/images/features/example_net%5B1%5D.jpg)

Frank and Adam are network “stars,” but Ken is a bridge, and his position in the network may be more important for diffusion of information. Figure adapted from Valente, T. W., & Fujimoto, K. (2010). Bridging: Locating critical connectors in a network. Social Networks, 32, 212-220.

Khanna cautions that lessons learned about the community on the South Side won’t automatically translate to other HIV prevention fights elsewhere (Schneider works extensively with global health issues, particularly with HIV in India). They’re not looking for what physicists describe as a “grand unified theory,” Khanna says. Instead, they are looking for community-level solutions in a variety of settings, and themes that emerge across these settings. And there’s clearly a great reward in doing research that impacts people who live so close by. “Sometimes I pass by someone on the street,” he says, “and I wonder, is he part of my study?”